Where are the Zhou Enlais of Africa?

The life of the Chinese revolutionary and statesman holds leadership lessons for Africa

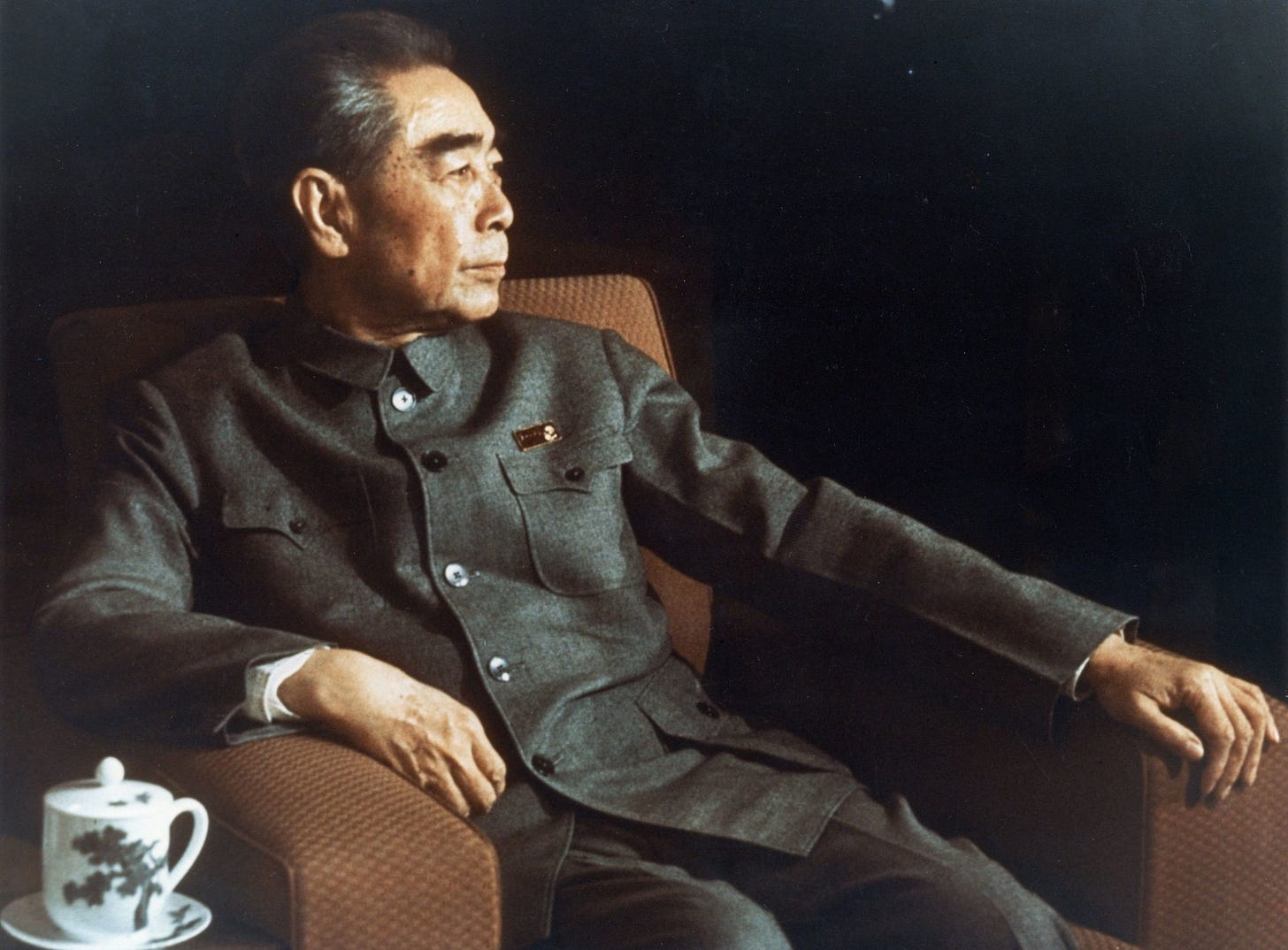

I just finished reading an incredibly impressive and detailed biography of one of my heroes, the Chinese revolutionary and statesman Zhou Enlai. The biography is titled Zhou Enlai: A Life and is written by the Chinese historian Chen Jian. Running at 840 pages (including a 100 pages of endnotes), the book is expertly written and provides a detailed year-by-year account of Zhou’s life from the time of his birth in 1898 until his death in 1976.

After spending close to 30 years building the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and leading the Chinese revolution alongside Mao Zedong and others, Zhou became the first Premier (Prime Minister) of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the year that the PRC was proclaimed. He held the position of Premier from 1949 until his death in 1976 representing over 50 years of uninterrupted service to the Chinese people (including the 30 years leading up to the proclamation of the PRC).

Zhou’s responsibilities as premier were dizzyingly wide-ranging. He was responsible for establishing and supervising the PRC’s sprawling bureaucracy and coordinating the many activities of the government and the CCP, which in a country with the geographic expanse and population of China was no small matter. Zhou was also at the center of coordinating China’s defence strategy.

If Chairman Mao was the philosopher king of the Chinese revolution, then Zhou Enlai was the one who implemented the chairman’s grand theoretical vision by reconciling different interests and overcoming reality’s binding constraints. It was painstaking work that only a patient bricklayer of Zhou’s temperament could do.

Of all of Zhou’s responsibilities, the ones that are enduring were his roles as de facto Minister of the Economy and Minister of Foreign Affairs. In the former role, Zhou authored many of China’s initial development plans that centered agriculture and industry. In the initial years of the PRC, Zhou acted as a wise and trusted intermediary between Mao and Joseph Stalin helping to secure crucial economic and technical assistance from the Soviet Union. At an important speech of the Third National People’s Congress in 1964, Zhou introduced his idea of the Four Modernisations and asserted that “in not too long a historical period, China would become an [economic powerhouse] with modern agriculture, modern industry, modern national defence, and modern science and technology” (page 520). 11 years later in 1975, the last year of his life, Zhou was even more definite when he declared, at the Fourth National People’s Congress, that “China would realize four modernizations in industry, agriculture, national defence, and science and technology by the end of the twentieth century” (page 681). How prescient he was!

Whatever his achievements on the economic front, it was on the international stage where his star shone brightly. In collaboration with India’s Jawaharlal Nehru, Zhou introduced in 1954 the “Five Principles of Peaceful Co-existence”, including the emphasis on mutual non-interference, that still guide the foreign relations of China today. In 1955, Zhou attended the landmark Bandung Conference where he delivered a memorable speech dispelling rumours of “red imperialism” and called on the people of Asia and Africa to join hands in fighting actual colonialism and imperialism. Zhou was decisive in providing strategic advice and facilitating military aid to Ho Chi Minh and the Vietnamese people in their historic defeat of the French and the Americans. In the early 70s, he masterfully handled the delicate negotiations that ultimately led to rapprochement between China and the US. Henry Kissinger, who had the misfortune of going toe to toe with Zhou in these negotiations, described Zhou as “one of the two or three most impressive men [he had] ever met” (page 635).

In 1964, Zhou undertook a friendship mission to Africa visiting 10 countries including Egypt, Morocco, Algeria, Mali, Guinea and Ethiopia among other countries. However, it was an incident leading up to his visit to Ghana that revealed Zhou’s fraternal feelings towards the people of Africa. Just before departing for Ghana, Zhou

suddenly learned that Ghana’s president, Kwame Nkrumah, had almost been assassinated in a failed coup. The security situation in Ghana was unclear, and all of Zhou’s associates believed that he should cancel the visit. However, Zhou refused to abandon the trip when the host [was] in temporary difficulty, not only deciding to go ahead with the visit to Ghana but also offering to meet with Nkrumah at his residence at Osu Castle. (page 501)

While in Ghana, Zhou announced eight principles that would guide China’s economic aid to other countries:

to provide the aid on the principle of equality and mutual benefit, never regarding such aid as unilateral alms; to strictly respect the sovereignty of the recipient countries, never attaching any conditions or asking for any privileges; to provide aid in the form of interest-free or low-interest loans and to extend loan periods in order to lighten the burden on the recipient countries; not to make the recipient countries dependent on China but to help them achieve self-reliance; to help the recipient countries build projects that require less investment but yield quicker results; to provide the highest-quality equipment and materials, and to replace the equipment and materials if they are not up to the agreed specifications and quality; to see to it that the personnel of the recipient country fully master the technology provided by China; and to ensure that the experts dispatched by China have the same standard of living as the experts of the recipient country. (page 502)

These eight principles continue to guide China’s foreign aid policies today.

Zhou was the glue that held China together during the tumultuous years of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. He brokered the return of Deng Xiaoping to Beijing after Deng’s purging during the Cultural Revolution. In the final year of Zhou’s life when he was practically bedridden, Deng often visited him and the two spent hours talking. Zhou likely shared the secrets of Chinese statecraft with Deng, a tutelage that shaped Deng’s transformative leadership of China.

One cannot put a price on the slow, steady and pragmatic leadership of the type that Zhou Enlai exhibited over the course of his long service to China and to humanity. This is precisely the kind of leadership that Africa is in desperate need of today.