Zambia As Experimental Subject

By Grieve Chelwa

Zambia’s debt talks have yet again hit a snag. This time around the hold-up is due to disagreements between official creditors, on the one hand, and private creditors on the other, with ordinary Zambians caught in the crossfire.

The basic gist of the latest hold-up is the following: For Zambia’s debt restructuring to succeed (i.e., provide sufficient fiscal room for us to grow ourselves out of the crisis), our creditors (the people we owe money) will have to take on “haircuts”. A haircut in finance is agreeing to accept less money than is owed. For example, if I owe $1 and find myself in a debt crisis and can’t pay back the full amount, my creditor and I can agree that I instead pay them back only 60cents ($0.60). That is, my creditor accepts to take on a loss of 40cents ($0.40) which translates into a 40% haircut.

Why would a creditor accept a haircut in the first place? Well because if they insist on my paying the full $1, they may end-up with nothing because my attempt to pay back the full amount may very well crash my economy to the point where all debt is unsalvageable. Therefore, haircuts, in times of debt distress, are not just important for the borrower but are also crucial for the creditor. In other words, the creditor is actually doing themselves a favour by offering the borrower a haircut.

In the particular case of Zambia, both official and private creditors have, unsurprisingly, agreed to take on haircuts. But the bone of contention is that the Zambian government has implicitly agreed to two different sets of haircuts for the two types of borrowers.

Analysis by Debt Justice, a civil society group, shows that official creditors had earlier agreed to a rather significant haircut of 45% with the Zambian government. On the other hand, the government, in a recently announced deal, seems to have promised private creditors a relatively generous haircut of 27%, which might even be as small as 3% if Zambia’s economy improves in the medium term!

This has naturally infuriated official creditors not least because it’s in violation of the so-called Comparability of Treatment Principle under the G20’s Common Framework. The comparability principle requires that private creditors take-on a haircut that’s at least as large as the one taken on by official creditors (i.e., a haircut of no less than 45%).

Why did the Zambian government think it wise to promise different sets of haircuts to different sets of creditors, a situation that would clearly violate comparability of treatment?

Perhaps naïvety about how the real world works on the part of our policymakers? Or incompetency?

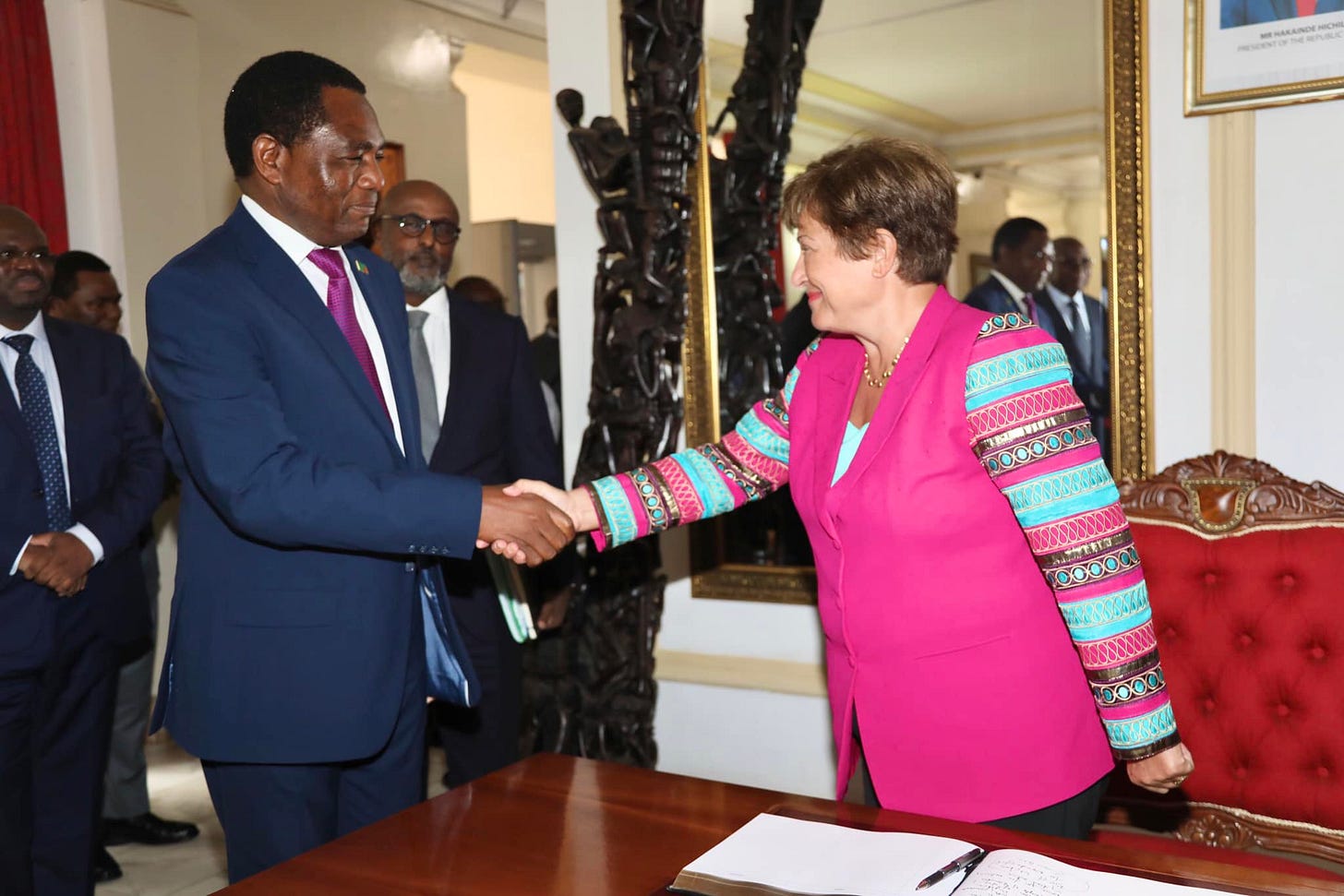

Or was this part of some geopolitical gamesmanship? For one thing, the official creditor that stands to lose the most from such a deal is China (holds the bulk of our official credit) while Western-allied private creditors (mostly bondholders) would stand to gain. Zambia, under the presidency of Hakainde Hichilema, seems to have pivoted its foreign policy allegiance to the Western bloc of countries (if in doubt have a look at the country’s most recent voting record in the UN General Assembly on those matters that are of geo-strategic interest to the West).

In any case, whatever the reasons, one thing that is increasingly clear is that Zambia is being used as an experiment to perfect the imperfect Common Framework.

It was easy to see from the outset that the the Common Framework, in its present form, wouldn’t deliver a speedy resolution to Zambia’s debt woes (I said as much in an appearance on Diamond TV in September of 2022). It was always going to be a drawn out process to use the Common Framework’s one-size-fits-all approach to resolve the specific case of Zambia’s debt given the varying set of creditors all with different preferences, interests and so on.

It is worth keeping in mind that a victory for the Common Framework would be a victory for the Western-dominated Global Financial Architecture — an architecture that periodically faces existential challenges because of its inherent contradictions.

But for the Common Framework to eventually work, it is necessary to pilot it on some backwater country like Zambia. It is merely a footnote that much harm is being inflicted on Zambians in the conduct of this grand experiment.

Grieve Chelwa is an Associate Professor of Political Economy at the Africa Institute and a Non-Resident Senior Fellow at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.