Africa's membership to the World Trade Organization has been a disaster

A pillar of neoliberalism has undermined Africa's ability to develop

The tariff wars of the last couple of weeks have been stunning to watch from Africa’s vantage point. It has been interesting to see tariffs, counter-tariffs and counter-counter-tariffs used as instruments of economic and geopolitical policy. This ability to use trade policy as a tool of statecraft is one African countries have been unable to wield largely because, unlike the rest, Africa takes seriously its membership to the World Trade Organization (WTO). And yet the WTO has been a disaster for the continent.

Headquartered in Switzerland, the WTO came into existence in January of 1995 with the ostensible goal of levelling the playing field for trade in goods, services and intellectual property. Effectively, though, the WTO, like its sister organizations the IMF and World Bank, has served the interests of rich and powerful nations at the expense of poorer and weaker ones. In the specific case of Africa, this has manifested itself in at least three ways: tariff policy, agricultural policy and imbalances in the WTO’s Dispute Settlement System.

Tariffs

A tariff is simply a tax on imports. With tariffs foreign producers face difficulties in accessing domestic markets. For this reason they have been used historically by governments throughout the ages as a tool for the protection of local producers against unfair competition from abroad. That is, as a tool of industrial policy. Nowhere else has the WTO effectively played its role as an underminer-in-chief of Africa’s development aspirations than in policies related to tariffs.

With the establishment of the WTO in 1995, African governments committed themselves to the reduction of tariff rates across the board and especially on manufactured goods. Figure 1 shows trends in the average tariff rates imposed on manufactured goods by African governments between 1990 and 2022.1 The figure shows three trend lines: average tariffs on manufactured imports from the world as a whole (blue line), average tariffs on manufactured imports from the US (red line) and average tariffs on manufactured imports from China (green line).

What is clear from Figure 1 is that average tariffs on manufactured imports into Africa have, in general, declined since the establishment of WTO in 1995. In the 4 to 5 years prior to WTO, manufactured imports from the world into Africa attracted tariff rates in the double digits that averaged about 19%. After the establishment of WTO, average tariffs declined precipitously into single digits and have stayed that way since.

One of the biggest beneficiaries of the establishment of WTO vis-à-vis Africa has been the US. As Figure 1 shows, the average tariff imposed on US manufactured imports into Africa declined from double digits to very low single digits post-WTO and stayed that way since. In actual fact, the tariff rate imposed on US manufactures has throughout this period remained lower than the world average and even lower than rates charged on Chinese imports.

Figure 1: Average Tariff Rates on manufactured imports into Africa, 1990 to 2022

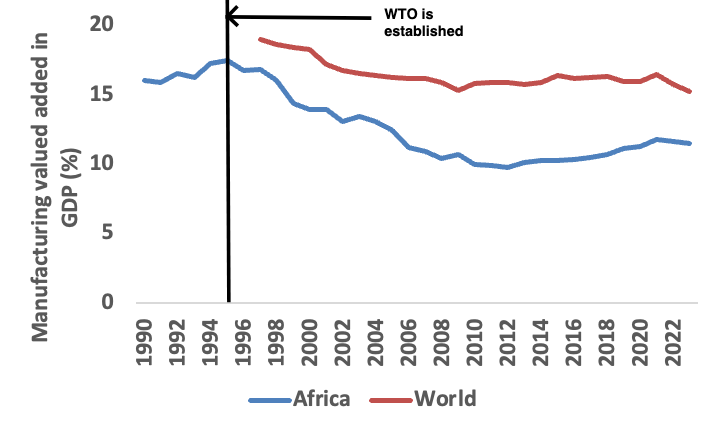

Naturally, this naked exposure of Africa’s nascent manufacturers to unfair global competition has had a devastating impact on the continent’s ability to industrialize. Figure 2 shows trends in the share of manufacturing value-added in GDP (a measure of industrialization) for the African continent and for the world as whole from 1990 to 2022. As is clear from the figure, the share of manufacturing value-added in African GDP was rising prior to the establishment of the WTO and declined thereafter. Further, the gap between Africa’s rate of industrialization and that of the rest of the world has grown wider post the establishment of the WTO.2 As history has taught us time and time again, industrialization is the only engine of development.

Figure 2: Manufacturing valued-added in GDP for Africa and the world, 1990 to 2022

You might ask: the majority of countries/regions in the world are subject to the WTO and, therefore, all were subject to declines in tariffs so why does this matter more for Africa than elsewhere? It matters because different regions were at different stages of industrialization/development at the onset of the WTO with Africa being the least industrialized region (read here, here and here to understand why Africa is the least industrialized region in the world). Exposing Africa to the same tariff shock as everywhere else effectively meant trapping the continent in a perpetual state of underdevelopment vis-à-vis the rest of the world. Alexander Hamilton, who was the first US Treasury Secretary in the late 18th Century famously argued for tariffs to protect America’s then infant industries against more sophisticated competition from Britain.

A second question you might ask is: why doesn’t Africa just ignore the WTO and levy higher tariffs like the US is doing right now? Well, unlike many other parts of the world, Africa’s economic policies are effectively designed, implemented and monitored by that other pillar of neoliberalism, and the WTO’s close relative, the International Monetary Fund.

Agricultural Policy

There are additional ways in which the WTO has trapped Africa in poverty. For example, the Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) that was promulgated as part of the establishment of the WTO in 1995 was meant to level the playing field for agricultural livelihoods and food security across the world via the reduction of “market distorting” subsidies. However, the the AoA was effectively drafted by the US and Europe and unsurprisingly both have continued subsidizing their often wealthy farmers at the expense of agricultural development in Africa and other parts of the global South.

Dispute Settlement System

Finally, you’d think that the African continent might make use of the WTO’s Dispute Settlement System (DSS) to, for example, challenge the violation of the AoA by the US and Europe. In principle, the DSS is supposed to provide equal access to justice for all its members. In practise, however, power and resource imbalances have meant that the rich and powerful have had more access to the DSS and, therefore, disciplined the rest. Since 1994, only two African countries have initiated disputes under the DSS. Over the same period, the US and the European Union have used the DSS over four hundred times between the two of them.

Whereas others have continued to use trade policy as a tool of industrial, economic and geopolitical policy in blatant violation of the WTO’s founding agreements, Africa has been a star pupil of the WTO studiously implementing its protocols. What have we gotten in return? Well, the appointment of our very own Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala as the first African boss of the WTO. Something to celebrate, I guess. Never mind her checkered history.

Technically, it is a weighted average tariff rate with the weights proportional to the volumes of trade of sub-categories. Additionally, Africa here refers to the so-called sub-Saharan Africa which is the, strangely, preferred way in which multilateral entities like the World Bank compiles data for the African continent.

Unfortunately, the World Development Indicators database doesn’t have data on manufacturing value-added for the entire world prior to 1997.